Minimax

Minimax (sometimes minmax) is a decision rule used in decision theory, game theory, statistics and philosophy for minimizing the possible loss for a worst case (maximum loss) scenario. Alternatively, it can be thought of as maximizing the minimum gain (maximin). Originally formulated for two-player zero-sum game theory, covering both the cases where players take alternate moves and those where they make simultaneous moves, it has also been extended to more complex games and to general decision making in the presence of uncertainty.

Contents |

Game theory

In the theory of simultaneous games, a minimax strategy is a mixed strategy which is part of the solution to a zero-sum game. In zero-sum games, the minimax solution is the same as the Nash equilibrium.

Minimax theorem

The minimax theorem states[1]:22:

For every two-person, zero-sum game with finitely many strategies, there exists a value V and a mixed strategy for each player, such that (a) Given player 2's strategy, the best payoff possible for player 1 is V, and (b) Given player 1's strategy, the best payoff possible for player 2 is −V.

Equivalently, Player 1's strategy guarantees him a payoff of V regardless of Player 2's strategy, and similarly Player 2 can guarantee himself a payoff of −V. The name minimax arises because each player minimizes the maximum payoff possible for the other—since the game is zero-sum, he also maximizes his own minimum payoff.

This theorem was established by John von Neumann,[2] who is quoted as saying "As far as I can see, there could be no theory of games … without that theorem … I thought there was nothing worth publishing until the Minimax Theorem was proved".[3]

See Sion's minimax theorem and Parthasarathy's theorem for generalizations; see also example of a game without a value.

Example

| B chooses B1 | B chooses B2 | B chooses B3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A chooses A1 | +3 | −2 | +2 |

| A chooses A2 | −1 | 0 | +4 |

| A chooses A3 | −4 | −3 | +1 |

The following example of a zero-sum game, where A and B make simultaneous moves, illustrates minimax solutions. Suppose each player has three choices and consider the payoff matrix for A displayed at right. Assume the payoff matrix for B is the same matrix with the signs reversed (i.e. if the choices are A1 and B1 then B pays 3 to A). Then, the minimax choice for A is A2 since the worst possible result is then having to pay 1, while the simple minimax choice for B is B2 since the worst possible result is then no payment. However, this solution is not stable, since if B believes A will choose A2 then B will choose B1 to gain 1; then if A believes B will choose B1 then A will choose A1 to gain 3; and then B will choose B2; and eventually both players will realize the difficulty of making a choice. So a more stable strategy is needed.

Some choices are dominated by others and can be eliminated: A will not choose A3 since either A1 or A2 will produce a better result, no matter what B chooses; B will not choose B3 since some mixtures of B1 and B2 will produce a better result, no matter what A chooses.

A can avoid having to make an expected payment of more than 1/3 by choosing A1 with probability 1/6 and A2 with probability 5/6, no matter what B chooses. B can ensure an expected gain of at least 1/3 by using a randomized strategy of choosing B1 with probability 1/3 and B2 with probability 2/3, no matter what A chooses. These mixed minimax strategies are now stable and cannot be improved.

Maximin

Frequently, in game theory, maximin is distinct from minimax. Minimax is used in zero-sum games to denote minimizing the opponent's maximum payoff. In a zero-sum game, this is identical to minimizing one's own maximum loss, and to maximizing one's own minimum gain.

"Maximin" is a term commonly used for non-zero-sum games to describe the strategy which maximizes one's own minimum payoff. In non-zero-sum games, this is not generally the same as minimizing the opponent's maximum gain, nor the same as the Nash equilibrium strategy.

Combinatorial game theory

In combinatorial game theory, there is a minimax algorithm for game solutions.

A simple version of the minimax algorithm, stated below, deals with games such as tic-tac-toe, where each player can win, lose, or draw. If player A can win in one move, his best move is that winning move. If player B knows that one move will lead to the situation where player A can win in one move, while another move will lead to the situation where player A can, at best, draw, then player B's best move is the one leading to a draw. Late in the game, it's easy to see what the "best" move is. The Minimax algorithm helps find the best move, by working backwards from the end of the game. At each step it assumes that player A is trying to maximize the chances of A winning, while on the next turn player B is trying to minimize the chances of A winning (i.e., to maximize B's own chances of winning).

Minimax algorithm with alternate moves

A minimax algorithm[4] is a recursive algorithm for choosing the next move in an n-player game, usually a two-player game. A value is associated with each position or state of the game. This value is computed by means of a position evaluation function and it indicates how good it would be for a player to reach that position. The player then makes the move that maximizes the minimum value of the position resulting from the opponent's possible following moves. If it is A's turn to move, A gives a value to each of his legal moves.

A possible allocation method consists in assigning a certain win for A as +1 and for B as −1. This leads to combinatorial game theory as developed by John Horton Conway. An alternative is using a rule that if the result of a move is an immediate win for A it is assigned positive infinity and, if it is an immediate win for B, negative infinity. The value to A of any other move is the minimum of the values resulting from each of B's possible replies. For this reason, A is called the maximizing player and B is called the minimizing player, hence the name minimax algorithm. The above algorithm will assign a value of positive or negative infinity to any position since the value of every position will be the value of some final winning or losing position. Often this is generally only possible at the very end of complicated games such as chess or go, since it is not computationally feasible to look ahead as far as the completion of the game, except towards the end, and instead positions are given finite values as estimates of the degree of belief that they will lead to a win for one player or another.

This can be extended if we can supply a heuristic evaluation function which gives values to non-final game states without considering all possible following complete sequences. We can then limit the minimax algorithm to look only at a certain number of moves ahead. This number is called the "look-ahead", measured in "plies". For example, the chess computer Deep Blue (that beat Garry Kasparov) looked ahead at least 12 plies, then applied a heuristic evaluation function.

The algorithm can be thought of as exploring the nodes of a game tree. The effective branching factor of the tree is the average number of children of each node (i.e., the average number of legal moves in a position). The number of nodes to be explored usually increases exponentially with the number of plies (it is less than exponential if evaluating forced moves or repeated positions). The number of nodes to be explored for the analysis of a game is therefore approximately the branching factor raised to the power of the number of plies. It is therefore impractical to completely analyze games such as chess using the minimax algorithm.

The performance of the naïve minimax algorithm may be improved dramatically, without affecting the result, by the use of alpha-beta pruning. Other heuristic pruning methods can also be used, but not all of them are guaranteed to give the same result as the un-pruned search.

A naïve minimax algorithm may be trivially modified to additionally return an entire Principal Variation along with a minimax score.

Lua example

function minimax(node,depth) if depth <= 0 then -- positive values are good for the maximizing player -- negative values are good for the minimizing player return objective_value(node) end -- maximizing player is (+1) -- minimizing player is (-1) local alpha = -node.player * INFINITY local child = next_child(node,nil) while child = ~nil do local score = minimax(child,depth-1) alpha = node.player==1 and math.max(alpha,score) or math.min(alpha,score) child = next_child(node,child) end return alpha end

Pseudocode

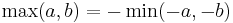

Pseudocode for the Negamax version of the minimax algorithm (using an evaluation heuristic to terminate at a given depth) is given below.

The code is based on the observation that  . This avoids the need for the algorithm to treat the two players separately.

. This avoids the need for the algorithm to treat the two players separately.

function integer minimax(node, depth)

if node is a terminal node or depth <= 0:

return the heuristic value of node

α = -∞

for child in node: # evaluation is identical for both players

α = max(α, -minimax(child, depth-1))

return α

Example

Suppose the game being played only has a maximum of two possible moves per player each turn. The algorithm generates the tree on the right, where the circles represent the moves of the player running the algorithm (maximizing player), and squares represent the moves of the opponent (minimizing player). Because of the limitation of computation resources, as explained above, the tree is limited to a look-ahead of 4 moves.

The algorithm evaluates each leaf node using a heuristic evaluation function, obtaining the values shown. The moves where the maximizing player wins are assigned with positive infinity, while the moves that lead to a win of the minimizing player are assigned with negative infinity. At level 3, the algorithm will choose, for each node, the smallest of the child node values, and assign it to that same node (e.g. the node on the left will choose the minimum between "10" and "+∞", therefore assigning the value "10" to itself). The next step, in level 2, consists of choosing for each node the largest of the child node values. Once again, the values are assigned to each parent node. The algorithm continues evaluating the maximum and minimum values of the child nodes alternately until it reaches the root node, where it chooses the move with the largest value (represented in the figure with a blue arrow). This is the move that the player should make in order to minimize the maximum possible loss.

Minimax for individual decisions

Minimax in the face of uncertainty

Minimax theory has been extended to decisions where there is no other player, but where the consequences of decisions depend on unknown facts. For example, deciding to prospect for minerals entails a cost which will be wasted if the minerals are not present, but will bring major rewards if they are. One approach is to treat this as a game against nature (see move by nature), and using a similar mindset as Murphy's law, take an approach which minimizes the maximum expected loss, using the same techniques as in the two-person zero-sum games.

In addition, expectiminimax trees have been developed, for two-player games in which chance (for example, dice) is a factor.

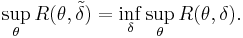

Minimax criterion in statistical decision theory

In classical statistical decision theory, we have an estimator  that is used to estimate a parameter

that is used to estimate a parameter  . We also assume a risk function

. We also assume a risk function  , usually specified as the integral of a loss function. In this framework,

, usually specified as the integral of a loss function. In this framework,  is called minimax if it satisfies

is called minimax if it satisfies

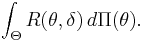

An alternative criterion in the decision theoretic framework is the Bayes estimator in the presence of a prior distribution  . An estimator is Bayes if it minimizes the average risk

. An estimator is Bayes if it minimizes the average risk

Non-probabilistic decision theory

A key feature of minimax decision making is being non-probabilistic: in contrast to decisions using expected value or expected utility, it makes no assumptions about the probabilities of various outcomes, just scenario analysis of what the possible outcomes are. It is thus robust to changes in the assumptions, as these other decision techniques are not. Various extensions of this non-probabilistic approach exist, notably minimax regret and Info-gap decision theory.

Further, minimax only requires ordinal measurement (that outcomes be compared and ranked), not interval measurements (that outcomes include "how much better or worse"), and returns ordinal data, using only the modeled outcomes: the conclusion of a minimax analysis is: "this strategy is minimax, as the worst case is (outcome), which is less bad than any other strategy". Compare to expected value analysis, whose conclusion is of the form: "this strategy yields E(X)=n." Minimax thus can be used on ordinal data, and can be more transparent.

Maximin in philosophy

In philosophy, the term "maximin" is often used in the context of John Rawls's A Theory of Justice, where he refers to it (Rawls (1971, p. 152)) in the context of The Difference Principle. Rawls defined this principle as the rule which states that social and economic inequalities should be arranged so that "they are to be of the greatest benefit to the least-advantaged members of society". In other words, an unequal distribution can be just when it maximizes the mininum benefit to those who have the lowest allocation of welfare-conferring resources (which he refers to as "primary goods").[5][6]

See also

Notes

- ^ Osborne, Martin J., and Ariel Rubinstein. A Course in Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1994. Print.

- ^ Von Neumann, J: Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele Math. Annalen. 100 (1928) 295-320

- ^ John L Casti (1996). Five golden rules: great theories of 20th-century mathematics – and why they matter. New York: Wiley-Interscience. p. 19. ISBN 0-471-00261-5. http://worldcat.org/isbn/0-471-00261-5.

- ^ Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003), Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.), Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, pp. 163–171, ISBN 0-13-790395-2, http://aima.cs.berkeley.edu/

- ^ Arrow, "Some Ordinalist-Utilitarian Notes on Rawls's Theory of Justice, Journal of Philosophy 70, 9 (May 1973), pp. 245-263.

- ^ Harsanyi, "Can the Maximin Principle Serve as a Basis for Morality? a Critique of John Rawls's Theory, American Political Science Review 69, 2 (June 1975), pp. 594-606.

External links

- A visualization applet

- "Maximin principle" from A Dictionary of Philosophical Terms and Names.

- Play a betting-and-bluffing game against a mixed minimax strategy

- The Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures entry for minimax

- Minimax (with or without alpha-beta pruning) algorithm visualization - game tree (Java Applet)

- CLISP minimax - game. (in Spanish)

- Maximin Strategy from Game Theory